http://www.jefferyrenardallen.com/index.html

Beginning Chapters

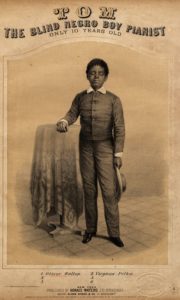

The book is loosely based on Thomas Greene Wiggins, a nineteenth century musical prodigy who played under the stage name Blind Tom. Tom was perhaps the most famous pianist of the nineteenth century. His celebrity was such that he played at the White House when he was ten years old, the first African American ever to perform there. He continued to perform for another thirty years?

The book opens in 1866 in the countryside near a city like New York where Eliza and Tom have spent the summer. They leave the country and set out for the journey by train to the City. Eliza must take precautions because Tom is the only black person living in the city. He has been living in hiding since the Civil War Drafts Riots (of 1863) erupted in the City. The black citizens, under attack, fled to the island of Edgemere. (This is my fictional exaggeration of true historical events.) Later, we see Eliza and Tom in the apartment where they live together. A white woman who is twenty-five years of age, Eliza is the widow of Tom’s former manager, Sharpe. Tom is sixteen.

Pairing: Champagne Pascal Doquet “Horizon” Brut Blanc de Blancs NV

http://www.champagne-doquet.com

Tasting Notes: Deep, rich aromas of yeast and lemon curd turn to flavors of sesame paste, lemon juice, and a seam of minerality that seems almost flinty. Excellent. Drink now – 2026+.

Middle Chapters

This is a flashback from the middle of the novel, although it goes back in time. Through shifts in point of view, these pages dramatize Tom’s stage performances, including his performance at James Buchanan’s White House in 1859. Part of the chapter is told through the eyes of Perry Oliver, Tom’s first manager. The final two scenes are conveyed through the eyes of his young assistant, Seven.

Quick note: in the opening paragraph, the third key is “A,” not E. That is, Tom is playing and singing three songs at once, each in a different key.

Pairing: Sonoma-Cutrer, Sonoma Coast Chardonay

Tasting Notes: Aromas of apple pie, Bosc pear and white peach are accented with oak spice, a hint of vanilla, toasted nuts, and a touch of butterscotch and light caramel. This wine has the distinctive Sonoma-Cutrer balance between elegance and richness for a medium-bodied, mouth-filling wine. The creamy richness has flavors of ripe apple, pear, peach and melon balanced with a bright acidity with lots of finesse. There is a long, silky finish highlighted with notes of roasted nuts and barrel spice.

End Chapters

As the novel ranges from Tom’s boyhood to the heights of his performing career, the inscrutable savant is buffeted by opportunistic teachers and crooked managers, crackpot healers, and militant prophets. In his symphonic novel, Jeffery Renard Allen blends history and fantastical invention to bring to life a radical cipher, a man who profoundly changes all who encounter him.

Pairing: Hendry Cabernet Sauvignon

Tasting Notes: Dense, dark berry color. In the initial aromas, pretty blackcurrant and caramel form the base notes, with soft cedar and black licorice. Very firm tannins portend a long life for this ripe, concentrated, dark wine. Decanting recommended to bring out the deeper, sweet fruit flavors and release the firm tannin grip; the wine becomes full and velvety with time and air.

Contemplation: Charleston Sercial Madeira

https://www.rarewineco.com/rare-wine-co-historic-series-madeira

Dense, dark berry color. In the initial aromas, pretty blackcurrant and caramel form the base notes, with soft cedar and black licorice. Very firm tannins portend a long life for this ripe, concentrated, dark wine. Decanting recommended to bring out the deeper, sweet fruit flavors and release the firm tannin grip; the wine becomes full and velvety with time and air.

Novel Excerpts

Beginning Excerpt

Had she missed the signs earlier? What has she done the entire day other than get some shut eye? (A catalogue of absent hours.) Imagine a woman of a mere twenty-five years sleeping the day away. (She is the oldest twenty-five year old in the world.) After Tom quit the house, she spent the morning putting away the breakfast dishes, gathering up this and that, packing luggage, orbiting through a single constellation of activities– labor sets its own schedule and pace—only to return to her room and seat herself on the bed, shod feet planted against the floor, palms folded over knees, watching the minute lines of green veins flowing along the back of her hands, Eliza contemplating what else she might do about the estate, lost in meditation so that she would not have to think about returning to the city, a longing and a fear. She dreaded telling Tom that this would be their last week in the country but knowing from experience that she must tell him, slow and somber, letting the words take, upon his return to the house for lunch; only fair that she give him a full week to digest the news, vent his feelings—in whatever shape and form– and yield. It takes considerable focus for her to summon up sufficient will and guilt to start out on a second search. Where should she begin? A thousand acres or more. Why not examine the adjoining structures–a tool shed, outhouse, and smokehouse lingering like afterthoughts behind the house, and a barn that looks exactly like the house, only in miniature, like some architect’s model, early draft. She comes around the barn—the horse breathing behind the stall in hay-filled darkness, like a nervous actor waiting to take the stage—dress hem swaying against her ankles, only to realize that she has lost her straw hat. A brief survey pinpoints it a good distance away, nesting in a ten-foot high branch. She starts for it—how will she lift that high?—when she feels a hand suddenly on her shoulder, Tom’s warm hand—Miss Eliza?—turning her back towards the house, erasing (marking?) her body, her skin unnaturally pale despite a summer of steady exposure, his the darkest of browns. (His skin has a deeper appetite for light than most.) He has been having his fun with her, playing possum—he moves from tree to tree–his lips quivering with excitement, smiling white teeth popping out of pink mouth. Tom easy to spot really, rising well over six feet, his bulky torso looming insect-like, out of proportion to his head, arms and legs–what the three years’ absence from stage has given him: weight; each month brings five pounds here, another five pounds there, symmetrical growth; somewhere the remembered slim figure of a boy now locked inside this seventeen-yearold (her estimation) portly body of a man–his clothes shoddy after hours of roughing it in the country—an agent of Nature—his white shirt green- and brown-smeared with bark and leaf stains.

Middle Excerpt

HE PLAYS “DIXIE” WITH HIS LEFT HAND IN THE KEY OF A, “Yankee Doodle” with the right in the key of E, and sings “The Girl I Left Behind Me” in the key of E. He plays the Moonlight Sonata with his back to the piano and his hands inverted. He plays a four- handed arrangement of Rossini’s Semiramide with two hands. He plays “Voices of the Waves” with his tongue and teeth, as if eating the ivory keys. He plays “The Rain Storm” in a minor key with his bare feet, walking melody across the black keys. He sings the song about his mother (“Mother, dear Mother, I Still Think of Thee”), and every woman in the audience starts crying. And now, ladies and gentlemen, Blind Tom will perform for you one of his own compositions, the latest from his growing catalog. Feel honored, ladies and gentlemen, as your ears will be the first to hear this beautiful tune outside my own. It is titled, and I assure you that you’ll see why, “Rattlesnake Charm.” Speaking slowly to get it right. You, Perry Oliver, the Manager of the Performance, call for a challenge from the audience. Who here in the house can make history by confounding Blind Tom? A man produces a composition of his own construction that he points out is some twenty pages in length. Please, sir, come to the stage. As soon as the challenger sets hands to his tune, Tom bends his head nearly to the floor and with one foot raised and stretched out behind him, begins to turn round and round upon the other foot, gaining speed as he spins, the entire figure agitated, rotating about itself on its own axis, performing implausible acrobatic contortions, in poses and expressions beyond the limits of the ridiculous and expressive. Now he begins to ornament the gyrations with spasmodic movements of the hands. He makes some members of the audience dizzy with his spinning. Some … 352 …

End Excerpt

There ain’t a goddamn thing that a person like you could do ever to stop me. Not today. Not tomorrow. Not never. Now, remove yourself from my presence. Go buy a farm. Go build a factory, or go do anything else you want with your worthless life. The General’s words go deep and draw out Perry Oliver’s history like a splinter in a finger. Seven is appalled. He vows: never (again) will he put himself in a position where he can so easily be humiliated, hurt, shamed, treated like a nigger. On the train afterward— after it is done, Tom relinquished, Tom gone— Perry Oliver keeps his gaze directed on the coach window, looking out at the passing world with a vision smudged with grief. (Seven looking as he looks, looking through his eyes.) Looking through not- tears at houses and barns, hills and valleys, lakes and rivers (the South, Confederacy, Dixie), scrolling countryside, birds untroubled in the sky, sunlight fractured by the thin trunks of tilting trees. Seven tries to hold the thought of Tom in his mind. Then the train takes a bend, and he can see through the window one coach linked to the next like sausages. Where does one begin and the other end? All those months moving together, all those years gone. (So the earth moves to make time.) And thinking thus sees the past shrink to a black dot behind them, him and Perry Oliver. Never forget. Never forgive.

Recent Comments